नवीनतम

नवीनतम

World Hepatitis Day: A handful of habits could protect your child

NEW DELHI [Maha Media]: In the world of public health, we often miss the forest for the trees. We obsess over surgical breakthroughs, high-tech diagnostics, and billion-dollar pharma solutions, forgetting that the biggest changes often come from small, almost invisible acts. Like the act of washing one’s hands.

World Hepatitis Day 2025

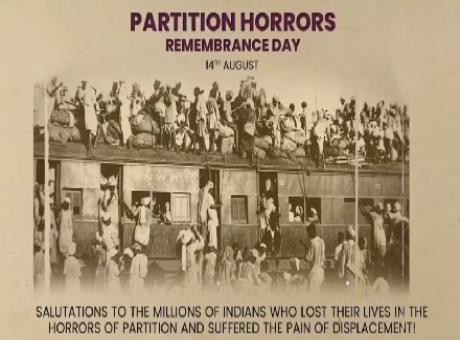

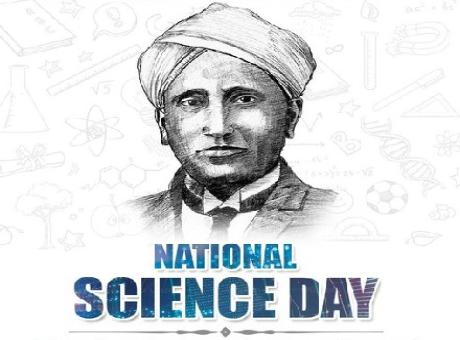

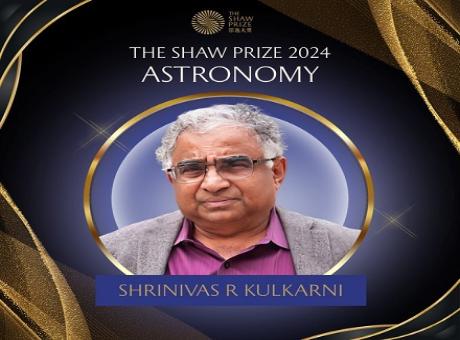

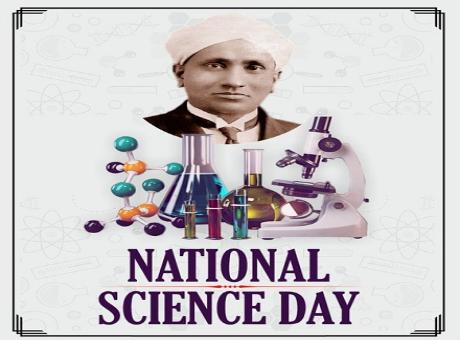

On July 28, the world pauses briefly to observe World Hepatitis Day. Hepatitis is that understated inflammation of the liver that kills more people every year than malaria or HIV. World Hepatitis Day is marked every year on July 28 for a special reason. It’s the birthday of Dr. Baruch S. Blumberg, the scientist who discovered the hepatitis B virus. He was born in 1925 in Brooklyn, New York. After serving in the U.S. Navy and studying medicine at Columbia University, he became interested in how diseases spread. His research took him to places like Nigeria, where he studied blood samples and found genetic differences that helped him eventually identify the hepatitis B virus. This major medical breakthrough earned him the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1976.

In 2024–2025, India reported 607 hepatitis-related deaths; 124 of them from Maharashtra alone. Hepatitis B and C continue to live inside 304 million people globally... most of whom don't even know it. The liver, perhaps our most overachieving organ, continues to suffer in silence. According to the WHO, fewer than half of the world’s babies received the hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of being born. That’s not a story about medicine. That’s a story about systems, access, and a kind of dangerous indifference.

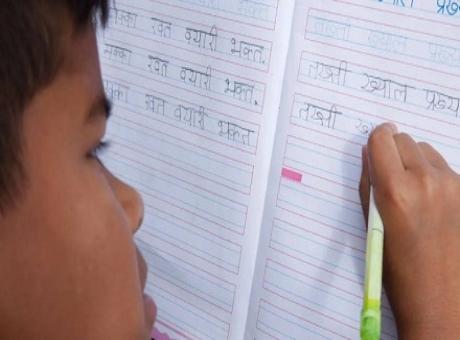

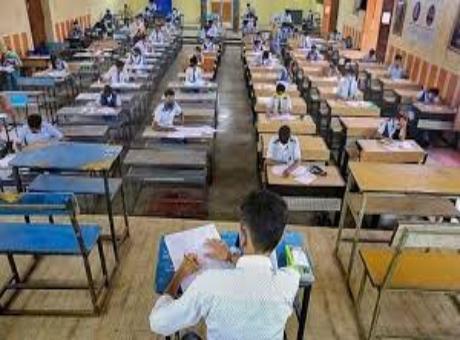

Consider a child in rural Gujarat or urban Mumbai. Her exposure to hepatitis A or E doesn’t begin in a hospital, but in the act of drinking water from a contaminated source, eating a mango sliced with unwashed hands, or touching a school desk smeared with invisible germs. Hepatitis A and E, unlike their more infamous siblings B and C, are not blood-borne. They’re fecal-oral. In other words: they travel through dirty hands, unclean toilets, and unsafe water.

So how do you fight a virus you can’t see?

The Rule of Small Things

In a world teetering under the weight of antibiotic resistance, pandemic fatigue, and health misinformation, the idea that soap and water can outperform a billion-dollar vaccine rollout is both humbling and revolutionary. Globally, 1.4 million hepatitis cases are reported every year. A significant portion of these are in children, especially in lower- and middle-income countries. But what’s stunning is how preventable these cases are. “The WHO estimates that just following hygienic food practices and ensuring access to clean water can cut the risk of hepatitis infections by more than half,” says Dr. Sai Kumar. That’s what behavioral economists might call a low-effort, high-reward intervention.

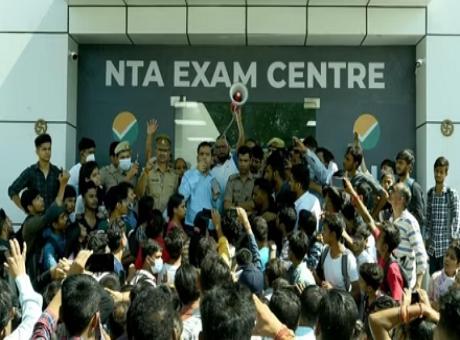

India’s Revolution

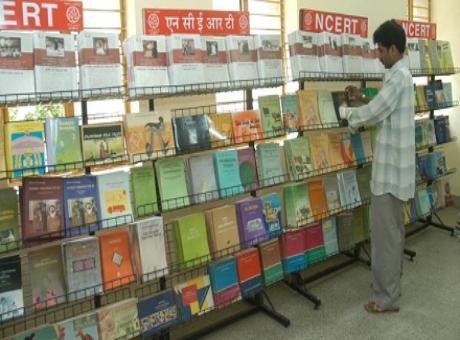

Now enter India’s National Viral Hepatitis Control Program (NVHCP), launched in 2018. On paper, it looks formidable: preventive, promotive, and curative measures; 978 treatment sites in 711 districts; over 10 crore people screened; and 3.3 lakh patients treated as of March 2024. It even integrates with maternal and child health programs, the National AIDS Control Program, and tuberculosis elimination efforts.

However, despite the reach and ambition, hepatitis still kills. Still sneaks into homes that don’t have running water or mothers who haven’t been told about vaccines. We have the infrastructure. What we’re missing is the nudge. In fact, 45% of newborns received the hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours in 2022. That means 55% did not. That window (the first 24 hours) is critical. After that, the protective effect diminishes.

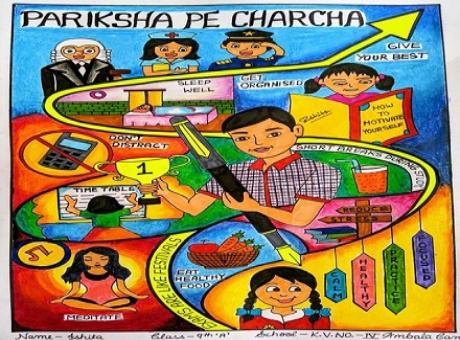

If there’s a bottomline to this story, it is this: Simple things matter. A basin with soap in a school canteen. A reminder in a vaccination booklet. A school teacher repeating “wash your hands” as often as she says “open your books.” The most effective intervention for hepatitis isn’t top-down, it’s sideways: sneaking in through habits, routines, and gentle reminders. It’s in parents who prioritize clean water. In schools that enforce lunch hygiene. In governments that remove friction from first-day vaccinations.